Healthy Drinking Week

The 7-week SKN Moves annual campaign, which started on 1st August 2023, continues with a focus this week on promoting healthy drinking habits.

The 7-week SKN Moves annual campaign, which started on 1st August 2023, continues with a focus this week on promoting healthy drinking habits.

We are delighted to share another article from our guest blogger, Teresa Coburn. Teresa is a registered nurse with 30 years of clinical experience. She is now using her expertise, knowledge and skills to create engaging and socially responsible health content.

Today’s blog post comes from Deji Ajose-Adeogun. Deji shares his 20-year battle with weight loss and explains how a recent change in mindset gave him the motivation and discipline to succeed in his quest to lose weight.

I have been dealing with being overweight since I left college. I never thought about what I was eating when I was younger because I was extremely active, so my eating was never an issue. Hours playing sports and lots of activity kept my weight in check. Well, as college finished and I proceeded out into the real world and got a job, my physical activity levels decreased drastically, but my way of eating did not change. So, I was eating more calories than I was burning. The math meant that I was going to gain weight. The pounds kept creeping up until last year when I topped out somewhere between 285-295 pounds. My clothes were not fitting me. Can you imagine that I left for college at 180 pounds, then I dropped to 165 in my first year of college. This was partly due to all the walking because that was the only mode of transportation and campus food was ok. Over the years, I have tried to lose weight. It has been like a yoyo, up one minute, down the next. This has been a battle for the last 20 years and it needs to end.

This is how the cycle has been. I joined the gym about 18 years ago, which I have been to on and off. One minute I am heavy with the gym, another minute I am not. In my 20’s it was easy to drop the weight, and it has also been a battle of the wits. When you lose that weight you start to feel good and like you can take on the world. Then you feel you can control it, and start back to old eating habits because I am lighter, next thing you know you are back up in weight again. Mind you, I thought I had it all under control. This is how the yoyo diet works. Your eating habits are only temporary until the weight is off. This is what it has been like for about 20 years. Then one day you say, “I give up” you start putting on weight, you get discouraged, you drown yourself in more food. It becomes self-defeating. I have been on cholesterol medication and blood pressure medicine. My doctor said I really need to do something about this so I am not on this medication for the rest of my life. I am not sure when it struck me. Was it my mom’s health situation and her passing in 2019? It might have been, but I knew that I had to deal with this immediately. I had to show my children, by example, what it means to eat well. I also have to be there for my kids, I know we are not promised tomorrow, but it did not mean getting there in a race car. It was embarrassing that I could not even get on a ride at an amusement park with my children about a year or two prior. I had to wait outside. I said to myself, the next time we came back, I am going on that ride with my children.

I had to figure something out that works for me and will not be a fad diet. I started to hear about intermittent fasting. I started to do more research to see if it will work for me. It involved fasting for 16 hours a day and eating in an 8-hour window. So, I would go from 8 pm to 12 pm the next day. This is a way of eating for many cultures. Some only eat one meal a day. The more I started to read about this way of eating, the more it made sense to me – the 16 hours give your organs a chance to rest and can help control blood sugar (as long as you are cutting back on sugars). I started eating more salads realising that what I was doing before had my organs constantly working.

I started in August 2019. The first month was a struggle, it was hard getting used to the new way of eating. I lowered my sugar intake drastically and ate more greens. I started to watch more videos about our diet and learnt that most people lack vitamin D, Vitamin K, potassium, good fats, good cholesterol, certain B vitamins, etc. I even started to learn that not all meats/proteins are good for you, partly because of all the chemicals and hormones in them. I started to try and eat as many organic items as possible. If not organic, anything that was less processed, such as farm-raised eggs, grass-fed cows, almond milk, etc. I started to eat out less and cook more.

There is so much more to losing weight than just eating less. It is also about eating correctly and getting the correct nutrients in your diet to help with your overall health. When I started to focus on health and not just weight loss that was the trick. Doing it for the right reason, my health, made me more disciplined and the pounds started to come off. I was not stressing if I did not lose the pounds, I was focused on just being healthier. Also measuring myself helped because you can gain muscle mass, which can mean your weight can remain the same, but your measurements can decrease.

At the end of the day for parents, it is key you teach your kids from a young age to eat properly, and exercise. You may want to exercise with them because that is where the habits will grow. It has taken me a lifetime to figure this out.

We would like to say a big thank you to Deji for sharing is weight loss story with us. We hope that through his experience, you can get a little bit of inspiration to help you achieve your weight loss goals. Have a question for Deji? Want to give him some encouragement? Then please do leave these in the comments section below.

Today’s blog post comes from Aaron D’Souza, a second-year medical student at the University of Medicine and Health Sciences in St. Kitts. While he has been active at school in multiple areas including playing soccer for the school and teaching high schoolers neuroscience with the BrainBee project, he is helping us as a new volunteer.

Today’s blog post comes from Aaron D’Souza, a second-year medical student at the University of Medicine and Health Sciences in St. Kitts. While he has been active at school in multiple areas including playing soccer for the school and teaching high schoolers neuroscience with the BrainBee project, he is helping us as a new volunteer.

Aaron discusses the emotions and challenges faced by caregivers of patients with multiple myeloma. By recounting his mother’s experience as a caregiver, he identifies barriers that a caregiver may struggle with and provides scientifically supported practical advice to help those who have recently become caregivers of a loved one with multiple myeloma.

Cancer is a group of diseases that everyone is familiar with in some form. Formally, it is the uncontrolled replication of cells leading to various problems. One particular cancer that will be the focus of this post is multiple myeloma (MM). Specifically, we will focus on the caregiver burden of those caring for someone with MM, as there is a lack of emphasis on their well-being and personal experience, but first, a bit of background information.

What is MM? MM is a type of blood cancer that is progressively debilitating, painful and ultimately fatal (most commonly due to infection).

Who is at risk? It occurs 1.6x more often in males than in females. It is 2x as often in the Black population than in the Caucasian population. Additionally, Black people are more likely to get it at a younger age.

When is it usually diagnosed? The median age of diagnosis is 65 years old. In cases diagnosed and treated early, 60% of patients will survive up to 5 years; only a fraction will survive 10 years after diagnosis.

What causes it? While there is a confirmed genetic role, there is also evidence of many other factors contributing to its onset. Such factors include exposure to radioactive substances and certain chemicals, such as benzene. Usually, a large dose of benzene can only be acquired from being exposed to factory emissions for several years or wastewater.

What are some symptoms? MM has systemic complications ranging from severe bone pain/ osteoporosis to kidney failure and infection. Throughout the progression of the disease and administration of treatment, it is standard to see periods of remission, periods of high severity and periods where the side effects feel worse than the disease.

Can it be treated? Sadly, the majority of people with MM will pass away. Recovery is possible if the patient is diagnosed early and started on therapy. Treatment ranges from conventional chemotherapy to stem cell transplantation. You can find more information on how these treatments work on the American Cancer Society’s website.

Unfortunately, MM patients are often misdiagnosed or are diagnosed late because there is a lack of experience diagnosing it among physicians. The latter happened with my grandfather, and within 1 year of diagnosis, he passed away. While many understand the suffering of a cancer patient, not many understand the challenges the caregivers face; a role that my mother fulfilled for my grandfather. A caregiver is someone responsible for the needs of the patient, often without any compensation. Responsibilities of a caregiver include scheduling, transport, finances, housekeeping, legal support and emotional support. It is usually a spouse, adult, child, or other immediate family members that fill this role and the role of a caregiver can be simultaneously rewarding and challenging.

My mother had her own mix of such emotions as a caregiver. At the time of my grandfather’s diagnosis, we had already lived in Canada for 10 years and in the United Arab Emirates before that, while my grandparents were living in India. Although my mom would go to India over the summers to look after my grandparents, she was otherwise dependent on friends and relatives to ensure my grandparents’ health and safety. The inability to be there with them for longer left her with a sense of guilt at the end of each summer, especially the last summer before my grandfather’s death. The uneven sharing of the caregiver role among family had placed an enormous strain on some of these relationships

As a caregiver, it is essential to note that uncertainty is the greatest obstacle for the well-being of both the patient and the caregiver. A caregiver’s well-being often reflects the status of the patient. Studies have identified numerous challenges to caregiver well-being. Most caregivers face at least a few of these challenges:

As a medical student who is always looking for ways to help people, I have found many coping strategies backed by evidence that worked for my mother and other caregivers. The following is a list of strategies, that as a caregiver, may help you provide the best possible care while looking after your own well-being:

Understanding and anticipating the challenges will allow you to avoid some of the anxieties associated with caregiving and better manage your time so you can spend it with your loved one. Keep in mind that every caregiver-patient relationship is different. There is more than one way to be a great caregiver. I hope the strategies above (which are by no means an exhaustive list) will go a long way in promoting caregiver well-being physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

We’re aiming to support multiple myeloma patients and their family members through the JAA Fund. Small support grants are currently available for patients in St Kitts, Nevis, the British Virgin Islands, Trinidad and Tobago. If you’ve been affected by multiple myeloma, live in one of these countries and require some financial support, you can apply for a grant here

Aksoy, M., Erdem, Ş., Dinçol, G., Kutlar, A., Bakioğlu, I., & Hepyüksel, T. (1984). Clinical Observations Showing the Role of Some Factors in the Etiology of Multiple Myeloma. Acta Haematologica, 71(2), 116-120. doi: 10.1159/000206568

Howell, D., Hart, R., Smith, A., Macleod, U., Patmore, R., Cook, G., & Roman, E. (2018). Myeloma: Patient accounts of their pathways to diagnosis. PLOS ONE, 13(4), e0194788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194788

Monterosso, L., Taylor, K., Platt, V., Lobb, E., Musiello, T., & Bulsara, C. et al. (2017). Living With Multiple Myeloma. Journal Of Patient Experience, 5(1), 6-15. doi: 10.1177/2374373517715011

Multiple Myeloma. (2020). Retrieved 11 September 2020, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/multiple-myeloma.html

Quiñoa-Salanova, C., Porta-Sales, J., Monforte-Royo, C., & Edo-Gual, M. (2019). The experiences and needs of primary family caregivers of patients with multiple myeloma: A qualitative analysis. Palliative Medicine, 33(5), 500-509. doi: 10.1177/0269216319830017

Waxman, A., Mink, P., Devesa, S., Anderson, W., Weiss, B., & Kristinsson, S. et al. (2010). Racial disparities in incidence and outcome in multiple myeloma: a population-based study. Blood, 116(25), 5501-5506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-298760

Today’s blog post comes from Mariana Ndrio. Mariana is a second-year medical student at the University of Medicine & Health Sciences (UMHS) in St. Kitts and is currently serving as the President of the American Medical Student Association (AMSA) on campus.

Today’s blog post comes from Mariana Ndrio. Mariana is a second-year medical student at the University of Medicine & Health Sciences (UMHS) in St. Kitts and is currently serving as the President of the American Medical Student Association (AMSA) on campus.

Mariana has recently started volunteering with us as a research assistant and is supporting us as we conduct our fibroids qualitative study. She is also creating a fibroids and COVID-19 infographic which will be published shortly.

Today, Mariana discusses the challenges that fibroids patients may be experiencing during this COVID-19 pandemic and shares some evidence-based self-care and stress management tips to help women with fibroids manage during this difficult period.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to prompt stressful changes to our daily routine and lifestyle, health-related worries regarding ourselves and loved ones have undoubtedly intensified. While the growing uncertainties stemming from financial difficulties and social isolation impact the health and personal decision-making of everyone across the globe, women suffering from uterine fibroids are facing unprecedented challenges in their attempts to preserve their mental and physical wellbeing.

Uterine fibroids are the most common benign tumours among women. While some cases of fibroids are accompanied by no side effects, other cases contain patterns of heavy menstrual bleeding, long and irregular periods, pelvic pressure and pain, constipation, frequent urination, and in rare occasions, infertility.

Treatment for fibroids can range from no treatment at all to surgery, depending on the severity of symptoms. Aside from apparent physical symptoms, the psychological impact of fibroids should not be disregarded. In a 2013 national survey of 968 women suffering from fibroids, 79% of the surveyed women expressed fear that their fibroids will grow or experience further health complications. According to a 2014 study assessing the emotional impact of fibroids half of the participating women reported feeling helpless and that they had no control over their fibroids, because of the difficulty managing and predicting the heavy menstrual flow.

Black women are 3 times more likely to become diagnosed with fibroids than white women, just as they are more likely to develop fibroids at a younger age; moreover, their fibroid size, frequency, and symptom severity are much greater.

As a medical student that remains generally impressed by the increasing amount of existing medical and scientific knowledge, researching gynaecological diseases such as fibroids have led me to a stark realization: that despite the high prevalence of uterine fibroids among women, not enough high-quality data is available to formulate evidence-based guidelines that address patients’ needs adequately. This points to a larger, unforgiving gap in medical knowledge pertaining to common diseases affecting women, and when combined with the gap in medical knowledge regarding COVID-19, a mixture of increased emotional stress and confusion is to follow. Such stress can hinder overall physical health and may exacerbate fibroid symptoms by influencing cycle length, vaginal bleeding patterns, and painful periods. If you are feeling uncertain or anxious, know that you are not alone; your worries and feelings are valid.

For that matter, we compiled some scientifically-backed tips that could be helpful in restoring a sense of control and ease in these difficult and unprecedented times.

While staying home and self-isolating is the best way to stay protected from COVID-19 and prevent the spread of the virus, this should not halt or compromise access to necessary medical care for women suffering from fibroids.

If you need to see a healthcare provider for a gynaecological reason, reach out to your medical provider and try to see if they are able to set up a virtual appointment or address non-urgent concerns over the phone (such as prescription refills).

While it is true that a lot of non-urgent appointments and elective surgeries are cancelled, many medical professionals and medical facilities are encouraged to use and have already embraced telehealth services which allow long-distance patient and clinician care via remote and virtual appointments, intervention, education, and monitoring. Telehealth services vary based on your location and medical provider. But even if you are having difficulties accessing gynaecological telehealth services locally, you might be able to reach out to service providers in other countries such as the U.K, U.S, or Canada. For example, USA Fibroid Centers provide virtual appointments you can schedule online. Women to Women OB GYN Care, located in Florida, states in their website that they welcome appointments from women internationally and the Caribbean. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) has also attempted to establish or expand telehealth services in a lot of Caribbean countries.

Keeping up to date with your prescribed medications can be confusing during a pandemic. You might feel like your regular access to your medical provider or pharmacy is compromised, you might worry that your current medications might be making you vulnerable to the COVID-19 or you might be feeling uncertain regarding the continuation of your current prescribed medications or supplements.

Nonetheless, it is important that you continue taking your prescribed medications and/or supplements unless otherwise advised by your physician. If you are receiving preoperative therapy (Zoladex, Lupron, etc.) but your surgery is cancelled, ask your physician regarding the course of your current prescribed therapy. If you have been prescribed a drug called Esmya (Ulipristal Acetate), you must consult with your physician regarding its discontinuation; as of 2020, Esmya’s license has been suspended due to the risk of serious liver injury. As mentioned previously, do not hesitate to discuss any concerns you might have regarding your current medications and supplements with your medical provider.

Studies show that women with fibroids might present heavier, prolonged bleeding and frequent, irregular periods. While everyone during a pandemic is worrying and trying to secure produce and disinfecting supplies, women suffering from fibroids have to also think about stocking up on female hygiene products. Especially, since frequent trips to the stores must be limited due to social distancing/quarantine rules.

Ensure that you have enough gynaecological hygiene products at home, to eliminate frequent trips to the store and avoid exposure to the virus. This by no means should be considered as the green light to go into a buying frenzy. Try to remain conscientious of the needs of others.

If buying hygiene products in bulk is not an option due to financial difficulty or store availability, reach out to local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or philanthropic entities, that might be willing to donate hygiene products such as the Days for Girls International Organization or even by reaching out directly to product manufacturers. Local grassroots organizations or associations in your region might also be able to donate hygiene items. Moreover, the governmental departments of public health or genders affairs might be willing to assist women in need of hygiene products.

This pandemic could also be a good time to consider reusable, more economical and environmentally friendly menstruation products such as washable pads, menstruation caps, or absorbent underwear. Check Days for Girls .org and learn how to make sanitary washable period pads during the COVD-19 pandemic, diligently following sanitary safety precautions.

Research has shown that following a healthy balanced diet, filled with fruits and vegetables, could lower the risk of developing fibroids and may help to alleviate symptoms.

While access to your usual healthy foods might be compromised at the moment, try to make healthy dietary choices while in quarantine. More specifically, dieticians recommend an increase in the consumption of cruciferous vegetables such as cabbage, broccoli, and kale. This category of food contains a phytochemical called indole-3-carbinol which recent research has suggested may prevent the cellular proliferation of fibroids and consequently prevent exacerbation of fibroid symptoms.

For many years, there has been a significant amount of scientific evidence that vitamin D may inhibit fibroid growth. Get your serum vitamin D levels tested and supplement (with medical supervision) as needed to correct a deficiency. A few recently published studies assessing the role of vitamin D against COVID-19, suggested that there is a possible link between the two and that vitamin D can have a protective effect against COVID-19.

Stay hydrated by consuming adequate amounts of water during the day and eliminate alcohol and caffeine. Researchers are advising women to avoid alcohol and caffeine because these substances are metabolized by the liver adding more stress on it and making it work less effectively at metabolizing oestrogen in the body. Additionally, amidst the COVD-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) urged the public to reduce alcohol consumption because alcohol compromises the body’s immune system and increases the risk of adverse health outcomes, making people more vulnerable to COVID-19. In other words, by cutting out alcoholic beverages, you are protecting yourself from adverse outcomes from both the COVID-19 and fibroids.

In addition, researchers believe that endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) which mimic oestrogen activity, may fuel fibroid growth. Examples include processed foods which contain various oestrogen-like preservatives; bisphenol A in water bottles, canned foods and plastic containers; various pesticides, herbicides, insecticides; and additive hormones and steroids used in meats and dairy products.

Try to choose organic, locally grown and in-season foods that are hormone and pesticide-free. Attentively wash any produce and peel fruits and vegetables. Reduce the use of plastics whenever possible and avoid reusing plastic water bottles or microwave food in plastic containers.

Research shows that a higher BMI – body mass index – is linked to the development of fibroids. By exercising you can reduce your BMI and prevent the fibroids’ growth. It may also help alleviate symptoms caused by fibroids. At the same time, exercise improves mental health by reducing anxiety, depression, and negative mood and by improving self-esteem.

Continue performing simple or recreational household chores and find an indoor workout routine such as yoga or aerobic exercises that you can perform at home while keeping up with the rules of quarantine. Choose what works best for you, based on your physical fitness and medical advice.

On days that you are feeling pain and other fibroid symptoms, rest up and give your body time to heal. Try to soothe cramps by applying heat and wear comfortable clothes.

It’s okay to spend a whole day in bed recovering. Be gentle with yourself and do not undermine what your body is trying to tell you.

We live in a society where time and productivity are precious and synonyms for money and self-worth. Yet, nothing is more precious than your physical and emotional well-being. Do not feel guilty for taking some time to rest and recover.

Although self-care looks different for everyone and should be based on your personal needs and situation, there are a few suggestions that could work for you and help you boost your mental well-being:

And remember, during these confusing and unprecedented times and while you are feeling that this pandemic is affecting you, in particular, a bit harder than the rest, there is always a community of women who are feeling exactly like you—you are not alone.

When it comes to the health and wellbeing of African people both on the continent and in the Diaspora at large, there are a number of challenges and health inequalities that exist. These inequalities include the black community having poorer health outcomes, being at an increased risk of developing a number of diseases and not always having access to adequate support to cope during periods of ill-health. In order to address these issues, many have suggested that the black community come together to develop solutions for us, by us. Before exploring unity as an approach to tackling some of these challenges, it’s useful to look back through history to understand the concept of unity so that if we are to come together, we develop partnership models that are most effective.

In today’s blog, we hear from guest blogger IC Blackman who takes us through the history of African unity and encourages us to think deeply about this concept.

One cannot deny the importance of an accurate grasp of history, particularly ancient history, for possessing a deeper understanding of our position, or lack thereof, in the world. Much has been argued about the relevance and authenticity of the terms ‘black’ or ‘African’ to describe peoples richly melanated in skin – for the purposes of demonstrative example as to the challenges of the realization of unity, we hold no fast consensus as to what we would prefer to be called. Arguments rage – all valid, I might add – for and against nomenclature that honours our history and invaluable contributions to the development and advancement of civilization. This begs the question: did we ever have a consensus, and if so, when, and how does this impact our concepts of Pan-Africanism, or black unity, today? The term to which one leans, whether black, African or some other, may be telling about how one views oneself vis-à-vis the world: identity, links to a certain landmass, being referenced as a colour or caste, and the legal implications and historical connotations of the latter.

To examine this predicament of a consensus beyond merely what we choose to be called, but in terms of the more pressing issue of unity, we ought to start from the beginning, or as close to the beginning as we can. Because of its startling symbolism, I choose to start with one of the most recent supercontinents and also the best known, Pangaea. There were other supercontinents that preceded it, but the further back I go, the more pushback I may get from certain scientific quarters about the presence of ‘thinking’ man in those times. Personally, I believe Homo sapiens sapiens is much older than the record books will allow.

As I describe certain geological phenomena in this post, one should also in tandem remember the Law of Correspondence. Hold tight – there is method to my madness.

The earth’s outer shell is made up of plates. Most activity occurs where plates meet or divide. Plates move in three ways: convergent (moving towards each other, even colliding in some instances), divergent (moving away from each other), and transform (where plates slide past each other). Movement of plates produces volcanic eruptions, underwater volcanoes, earthquakes, and, specifically by convergent plates, mountain ranges; thus, there are several cycles of creation and destruction, periods of volatility and rest, all natural, all inevitable, all a part of existence. The most volatile processes create new forms, it would seem, adding to the topographical features of the earth – mountains and valleys, the highs and the lows. Movement can occur slowly or violently, changing the architecture of Planet Earth. Each continent as we know it today rests on these plates, that is, tectonic plates. They are in constant motion and interaction, a process called plate tectonics.

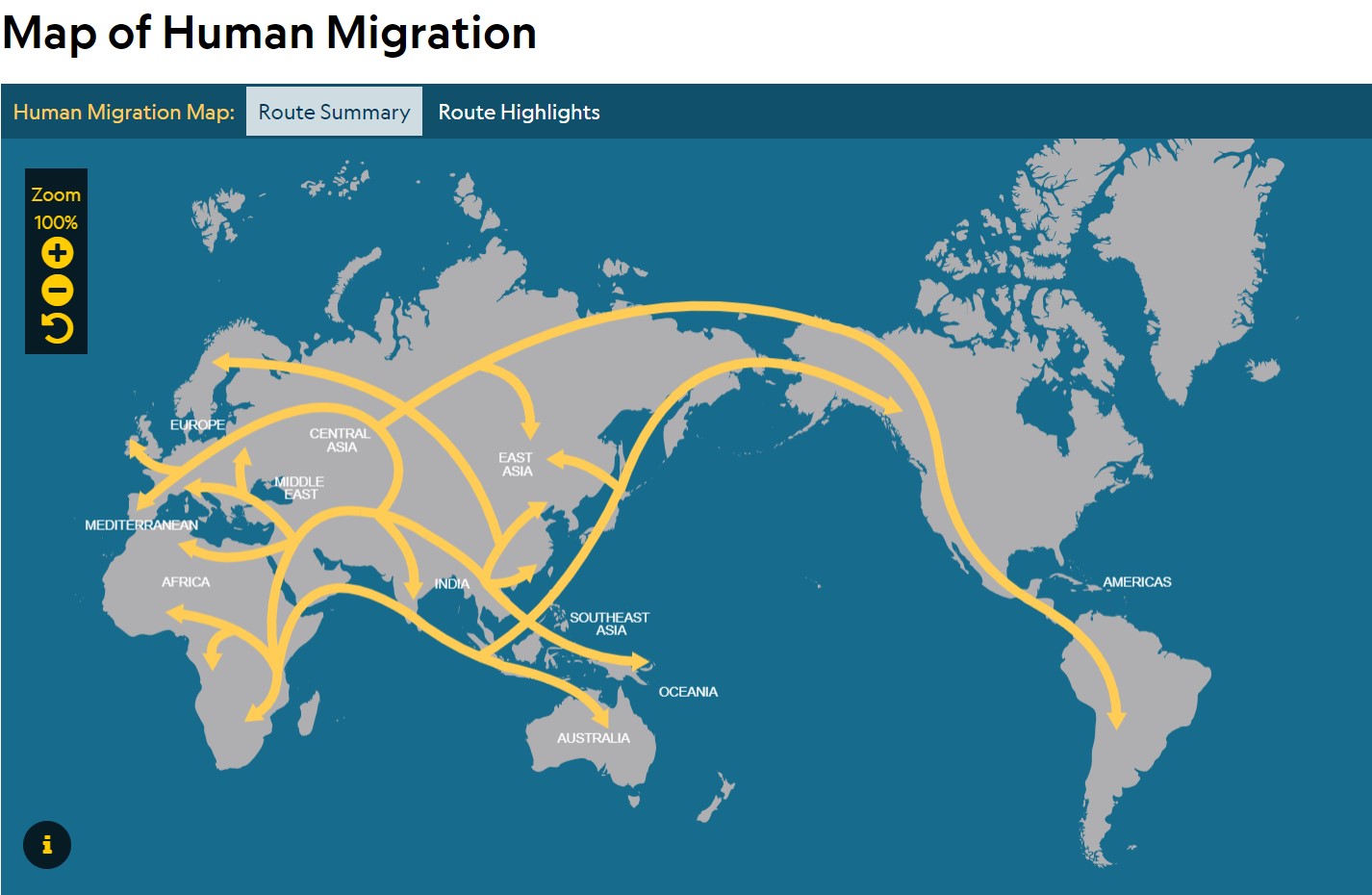

Using geological time collapse, let’s agree on a single landmass called Pangaea – a supercontinent, consisting of lakes and rivers, which existed before the latest continental drift, i.e. the divergent movement of major plates that created the large and distinct landmasses we call continents today, in their latest configurations and geographical locations. Let us also agree that easy human migration out of Africa was facilitated by the most recent supercontinent Pangaea and its many incarnations prior to the most recent and significant continental drift. We can further argue about the origins of the name Africa, but if we are to have a consensus about nothing else, it should be about coming to terms with the usage of this epithet.

Let us also observe the signature feature of African civilizations to form along rivers, the best known being the Nile Valley civilization, from its origins in the south heading down the Nile to the north, its pinnacle manifesting as Kemet or Egypt. It is important to note here that rift valleys occur where a continental landmass is ripping itself apart – this happens in geological time. Modern Africa, i.e. the continent we know today, is projected to split along the Great Rift Valley system sometime in the very distant future, forming a double continent. In other words – change is supreme, movement is inevitable.

And like nature, like tectonic plates, we as a people are in constant motion, a constant state of flux, producing what I call the Dispersion Factor. This first manifested as migration to all continents before they were so-called, and the subsequent development of distinct civilizations on these landmasses after continental drift. One mindset, but a myriad of manifestations. Physical unity, then, would seem to go against this natural tendency towards dispersion and dissemination, as opposed to the more challenging but urgently needed spiritual and mental/thought unity.

Encoded in the DNA of African peoples may be the genetic roadmap for dispersion and multicentricity. We know that Africans as a group have more variations in their DNA within their group than between Africans and other groups. This phenomenon of what I call genetic non-cohesion may well be the reason why breeding farms in chattel slavery in the New World, which used a high degree of consanguinity, could produce ‘normal’ populations for far longer than logic would dictate. It could also be the reason why as a group we will adapt, include, and assimilate with ease. The downside is that this will occur in hostile as well as conducive environments, the former producing cultural distortion and disintegration, the latter producing cultural catalysts. There is no doubt that both processes have global knock-on effects and implications. We do ourselves a disservice to underestimate the profound effect of our state of being, both positive and negative, on the planet at large.

It’s very conceivable that the theory of Pangaea holds true – at the very least, it makes perfect sense. If you look at all the continents on the planet, they do appear to potentially fit together, much like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Let’s continue to entertain the Law of Correspondence here. It is also conceivable that man existed at the time of Pangaea, or a forme fruste of Pangaea, and migrated outward from a pivotal focal point of creation. I call this point, adapting a term from embryological science, the pluripotent stem cell, from which all major cells of the human body originate – the pluripotent locus, or the progenitor cell from haematological science, the mother cell of all haematological bodies (red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, etc.). These cells, being multi-hued and multi-functional, together form an efficient body system. That pluripotent locus, or primogenitor cell, we know today as the continent of Africa, remembering that it was once part of a contiguous landmass. For those who want to call it the Garden of Eden, I have no ready rebuttal. Whatever we choose to name this pivotal location, we must appreciate that now these disparate landmasses have been christened continents with bestowed names, some of which have changed over time, e.g. India was once Hindustan, and perhaps the continents were perceived differently prior to continental drift and after it, including in name.

Map courtesy National Geographic

Map courtesy National Geographic

Anthropological evidence and copious historical data would indeed confirm an ‘African’ presence on what we now know as the seven continents. Perhaps more accurate would be First Man and Woman, Ancient or Aboriginal Peoples. Genetics would suggest they were very diverse people.

Herein lies Ponder Point No. 1. This multifocal presence and the early civilizations it birthed aren’t as well-known as one would think. It certainly isn’t taught on the scale it should be, despite the evidence to support it. Africans therefore have been as a group multicentric, dispersed, and migratory from their very inception, and have had varying phenotypes, and within recent times, lighter hues in certain regions of the Earth. They set up civilizations wherever they landed – the Indus Valley civilization, the Nile Valley civilization, the Olmec civilization – and kept it moving. This has been a modus that has taken many incarnations throughout history, and up until modern times, it does not seem to have slowed, though immigration laws have had an impact on the freedom of movement enjoyed in antiquity.

The push and pull factors that sustain such movement are however very different, perhaps more unfavourable, but not at all exclusive to negative experience, than in the past – pioneering waves of voluntary, exploratory migration vs the more recent exploitative waves of forced migration. Ponder Point No. 2 eagerly cranes its neck for keen observation – the concept of unity, especially physical unity, I would therefore challenge further, is a very tenuous one. We tend to use ‘Africa’ as one would a collective noun, but there would be no harm in saying one was African and Senegalese, for example, or African and Ghanaian, or African and Guyanese, understanding that as one leaves the continent more qualification is required. You may also want to add Christian or Muslim, for example. We should be used to complexity by now. We’ve been here from the beginning. Our history is complex – multilayered, multidimensional, multifocal, and multiethnic. We’ve been here from the beginning – it is complex. And that complexity lends itself to both confusion and a timely consecration. One would be more inclined to speak of, and place greater store on, a core African mindset with its many global manifestations, i.e. cultural diversity even within the collective – on the mother continent of Africa, and in the Diaspora at large. Here, we may need to entertain further clarification and qualification of an ancient vs a modern Diaspora.

And while we’re at it, we may also need to make a distinction between ancient Africans and modern Africans (an ever-evolving entity). A distinction also needs to be made, using a chronological timeline, as to when this conversion – ancient to modern – took place. I would set that time at 1492 and the expulsion of the Moors from what we now know to be Spain – the Iberian Peninsula may be a more accurate term. For this pivotal historical event would generate a series of further historical events – the Spanish Inquisition and the Crusades, chattel slavery, colonialism and neocolonialism. All these would produce the modern African, who would be designated many names and pseudonyms through space and time, all with a growing patina of mistrust, disrespect and contempt (I’ve excluded some for good reason) – Ethiops, Ethiopian, Maure, Moor, blackamoor, Negro, black.

Superimposed on this, and perhaps contributing to our wounding in 1492, subsequent conquest and present predicament, we must also appreciate ancient African civilizations in decline, their peak in Kemet (Egypt). These would include the fall of the empires of Kush, Mali, Benin, Axum and Songhai and the kingdoms of Ghana and Mossi, and the phenomenon of infighting amongst nations and their weaker neighbours, a growing insularity of thought and the emergence of maladaptive forms of self-preservation in response to repeated foreign invasion. This decline, and it would happen over millennia, would also herald a new African, or modern African, and a new Africa. Stronger nations usurped weaker ones, and their captives, the spoils of war or POWs, created fodder for the transatlantic slave trade. Empires fell due to loss of life and loss of intellectual property, the draining of resources, human and mineral, brain and brawn. We, however, seem to have moved from physical wars and battles to ideological ones with physical elements and consequences – wars of class, wars of colour, wars of identity, fueled by hubris, greed, deception, envy and a forgotten self-knowledge.

All of these could be significantly ameliorated if we saw ourselves as privileged beyond the banal or the physical. One would argue these character chinks and ideological imbroglios were with us before 1492 – that we grappled with these human failings more and more as civilizations declined over time – but were exacerbated, perhaps entrenched by the Maafa. If one studies African mythology deeply in all its facets, for example Yoruba or Akan – the roadmap that would assist us in this journey of becoming whole or indeed returning to wholeness – they all address these human foibles.

One would argue that the first real unification or semblance of physical unity occurred in the West, i.e. the Americas, and under horrific conditions – nations and empires gelling under the remit of one plantation and one master. Ponder Point No. 3: is there any doubt, therefore, as to why unity is such a challenge? In a thriving plantocracy, betrayal was rewarded – the Meritorious Manumission Act of 1710 – while gathering in public was punishable by death, that is, laws prevented congregation. Non-cohesion was ratified in law.

But was ancient African success ever leveraged on physical unity, or was it a unity of mind and principles, a spiritual unity – a quantum mindset/thought, intangible yet effective? Certainly, unity, if it is to occur at all, would not be sustained if forged from the negative – anger, hate, dissatisfaction or a preoccupation with adversity, that is, under duress. (The adversity, however, should be recontextualized as a perfecting catalyst, refining thought back to the depths of the visionary, the mystic and the natural scientist. Challenging? Absolutely.) But take heart, this volatile process of unification seems to mirror the earth.

Should we be seeing unity as the Ancients would suggest, that it isn’t about the physical at all? Is the challenge mental, internal, and will it eventually manifest naturally in our external world? Is this a call to transcend the physical domain and its vicissitudes and aim even higher, to a more symbolic existence beyond the mundane, beyond the constraints of a dominating cultural lens? Perhaps we fell low to rise higher than we’ve ever been – ascension. Perhaps it’s all in the mind – we should be in one mind. The time is now. If we don’t get it, who will?

More and more it would appear that as Africa and Africans go, so goes the earth. This is our life-altering inheritance as the Mother and Father. If there is to be any pre-occupation, it should be, how do we honour the Mother and Father? What does it look like, feel like, taste like, sound like? Is it truly all in the mind? How we perceive it may be everything. And here’s the good news – despite the Great Rift Valley divergence, the earth’s tectonic plates continue to move, their motion slowly bringing the continents together again. Pangaea will be re-formed, a new supercontinent by a different name that may bear little resemblance to the Pangaea of old. Symbolic? Think about that Law of Correspondence and rest your mind there – as within, so without; as without, so within. It would seem feasible to conclude that continental drift is as inevitable as its reversal. How quickly or slowly the process unfolds may be within our grasp; certainly the process of continental rift is. This is not a hypothesis, but an inevitable process that will also reverse, and at a pace we determine. You don’t have to agree, just consider.

©2019 IC Blackman

We would like to say a big thank you to IC Blackman for this very insightful blog piece. If you have any comments or questions, please leave them in the comments section below.

You can find out more about IC Blackman and her work here or you can follow IC Blackman on Twitter.

Today’s blog post comes from physician-writer, IC Blackman who began writing fiction in 2007 after embarking on a career break from working as a consultant physician in general internal and geriatric medicine. She is the founder of Dried Ink through which she has created a literary genre, Connected Fiction, to engender discussion between the young and the old.

IC Blackman discusses how our history, specifically slavery, has shaped our food culture and therefore impacted the health of black people today. This piece challenges us to reflect on why we eat the food we eat by exploring historical truth, to question our life choices and to move towards a simpler, healthier lifestyle.

Physician writers have a duty to combine their writing content with the breadth of their clinical experience. However, one’s life experience is equally as valid as that learnt from a career in medicine, which at its core is a profound, personally transformative science.

As physicians, we diligently and dutifully take detailed chronological medical histories of our patients, but these patients to whom we are entrusted are a microcosm of the much vaster realm of human experience. That experience is what we would summarily call world history. Every patient’s history is different and nuanced in its own way, coloured by cultural context, or identity, for those with enough sentience to grasp this salient concept. This is made that more challenging as we pen such histories and translate our patients’ spoken words into cryptic medical jargon. Most would focus on the pathological process at hand; the histories therefore are oftentimes tailored for disease, not health. In fact, they centre around elucidating cause and effect, and, at their very best, treating the cause, and not the myriad effects, which we call symptoms, signs and diagnostic criteria. Not to diminish the latter, as to miss one of these would be to risk a misdiagnosis and its subsequent tragic sequelae. We do, as a part of the history-taking exercise, include a dietary, social and family history which usually, but quite disappointingly, takes up less than a quarter of the entire ‘life story’ of the patient. Metaphysicians, naturopaths and medical intuitives may have great reservations about this – it should be at least 40% of the entire history, they would entreat, and I’m beginning to be a strong supporter of this; one would be remiss to disagree.

On this backdrop, then, one quite unexpectedly, yet with what would seem to be a natural extrapolation of clinical expertise, embarks on a continued journey, an intrepid adventure. Here one begins to translate the gamut of human experience into writing fiction as a physician writer, not just for entertainment but for studied consideration. Not for speedy conversions or to arrive at a diagnosis – though these may happen organically – but for the purposes of deep self-reflection, discussion, intergenerational connectedness and, ultimately, resolution of familial conflict. This then translates into broader avenues of harmonious living. Connected Fiction, a term I coined quite by happenstance in 2015 as it best described my committed purpose for writing, is an ambitious endeavour. Its primary aim is to bridge the disconnect between teens and the significant elders in their lives: mother-daughter, father-son, granddaughter-grandmother, teacher-student – the connections go on and on. This is deliberately constructed through compelling stories of many genres, buttressed by relevant themes and colourful characters…. Have I honoured my own maxims and utilized my clinical experience in fulfilling my purpose? Yes. To wit, have I used my personal experience as well? Absolutely, perhaps even more so. Will I succeed in my mission? Time will tell. History will record whether I do or do not… What is certain, though, is that any profit gained is for the reader and not necessarily for the writer. Profit here translates to healing, not so much monetary reimbursement.

My last novel, a collection of short stories, has as its source inspiration what appears to me to be part of an ongoing dilemma we have in the African Diaspora but not exclusively. This would be the under-appreciated connection between cultural identity, historical truth and the health of adults and children. I include mental health here as well. The mind controls the body, and if we are to ignore the mind, we would necessarily be setting ourselves up for a whirlwind of world hurt and poor health outcomes. In the novel, I use intergenerational female relationships as a vehicle for examining the aforementioned, as well as what we normalize as cultural ways of being – our values, principles, tastes, and daily preoccupations.

The enslavement of African peoples, as well as the indentureship of South Indian peoples, to fuel the industries of sugar, tobacco, coffee and cocoa, to name but a few, a poignant part of world history, has had long-term ramifications. Hitherto these have been seen only from an economic viewpoint; the psychological and mental impact have been given little global appreciation and in-depth examination. Some have explored the effects of chattel slavery and indentureship on sociopolitical superstructures and their inherent inequities and spawned ideologies. However, few have dared to draw a connection between mass production of these products and their byproducts, their effects on physical health in the very countries that provided free labour and fertile lands, and the psychological wounds which fuel their excessive consumption. All this, to make them some of the most profitable industries of the modern era, providing countries which held and still hold the means of production with immeasurable wealth.

The production of coffee, tobacco – for cigarettes – and sugar from sugarcane – for confectionery, drink and myriad foodstuffs – were all labour intensive exercises, the harvesting of cocoa for the production of chocolate even more so. Most of these products have high addictive potential – a phenomenon that needs further in-depth exploration. Once the existence of this phenomenon is agreed upon, it could change the way we offer and formulate any intervention to curb the present obesity crisis, not just in the former colonies of Empire that produced the raw materials, but also globally. Most are consumed in great amounts when coupled with psychosocial foibles and/or triggers – poor access to healthier options, fractured emotional bonds, subclinical depression, gaps in health education, and – let’s be clear – gaping holes in historical context. Little is taught about the history of the abject conditions under which these crops were grown and harvested, the lives maimed or indeed cut short by their production, and the wealth inequities they spawned, some of which still exist to this day. These historical truths hold the key to a much-needed reverence for these profitable, ‘seductive’ crops. Do we need to start embracing a mindset where we consider the products of these crops delicacies for very deliberate and sparing consumption? Should they be perceived much like, say, a rare aged cheese, or perhaps the eco-unfriendly, as now considered by some, Beluga caviar (not an analogy to be taken lightly), whether in their native state or in the food we consume daily? Should this then mark the opportune and perhaps urgent demise of the jumbo or family pack of any of these products – the colossal chocolate bar for instance, the litre bottle of carbonated drink? Size is everything. Portions may well predict posterity, or the lack thereof. Is everything edible to be classified as food? Is food to be defined as that which gives the body nourishment? Does the food pyramid need to be revised so as to exclude sweets? Should such products be purchased at much higher prices than ‘true food’? I deliberately exclude tobacco here for good reason. Historical truth is the segue to better health, if taught in a way that includes the inception, propagation and maintenance of these industries – cause and effect.

Then there arises, from the depths of free enterprise, the behemoth that is financial profit and the livelihoods of those still producing these crops today, something that cannot be circumvented easily. This naturally begs the questions – how much profit is reasonable profit? Should it be tariff-based or price-based or both? Should we be looking for other uses for these crops which don’t remotely include our gastrointestinal tracts and subsequent ill-health? Rooted in the answers to these questions, other questions follow – what does one value above one’s own health, and the health of a nation, and indeed the world? What are we sacrificing to achieve and maintain a ‘handsome profit’?

How does cultural identity play into all this, you might ask? Who would disagree that food – what we eat, how it is harvested and prepared, the where and the when – is a manifestation of culture? Must we now examine how much we inculcate another’s culture into our own, if said assimilation begins to produce adverse effects in the general population? It’s what I wistfully call cultural integrity – not to be confused with cultural exceptionalism, cultural exclusion and xenophobia. And one has to clarify what one means by inculcation – latter-day adoption without appropriate cultural translation. Has sugar ever played a major part in Caribbean cuisine, South Indian or African-derived? One could argue that chattel slavery introduced many dietary and indeed social habits which were compensatory, partly oppressive, and born from a culture of lack and a chronic functioning outside the realms of one’s cultural imagination. We made do. Innovated. As some would say, maladapted through forced choice – no choice at all – and under tremendous duress, not consent.

Deeper issues abound beyond faddism – going vegan or vegetarian, dry- January… One should note here, though, that South Asian Hindus maintained their veganism in indentureship through an intact religious ideology, and Muslims – either African or South Asian in origin – refrained from alcohol and pork. It was true during indentureship, and to a lesser extent during chattel slavery; true even now. But now that we are in a better position financially to embrace abundance, has that abundance translated dysfunctionally into excess, as a symbol of having ‘arrived’? Is obesity the new malnutrition of our age, replacing what we were familiar with in the Diaspora – marasmic kwashiorkor and protein energy malnutrition, usually an index of poverty, unlike obesity? Can we rein this in in time, given that we are yet to address the ongoing psychosocial issues that fuel excessive consumption, as mentioned previously in a by no means exhaustive list? Have we ever craved sugary or fatty foods in tropical climes? And if we do now and within the recent past, why? Is this solely driven by physical needs, or is it a reflection of the preponderance of psychological hunger? What quenches our thirst more in the hot sun – cool water or a sweetened drink, fruity or fizzy? When we have been blessed with a climate that fosters an outdoor lifestyle, why are we imprisoned indoors as if in a harsh winter? Is the rum shop a place for social gatherings, or a pharmacy for troubled minds? How much chocolate do we need to consume in order to feel loved, worthy, alive, spiritually and emotionally sated? How much coffee do we need to imbibe to get going, when perhaps what we truly need is to stop what we’re doing, reassess our life choices and make the necessary changes towards a simpler, more fulfilling existence? And how many cigarettes do we need to smoke before we say a premature goodbye, our breath of life snuffed out when we are in our prime?

Now that we understand that genetically as an ethnic group – African and South Asian – we metabolize sugar, salt and most substances with addictive potential differently, how do we honour that truth? These are not scientific secrets. Let’s look at our history. Let’s define culture clearly – what does it look like, feel like, and, not to veer off-topic, taste like? How does it align with our overall health – mental, physical, spiritual, and social? How do we take the best examples of healthy living from the many cultures that exist on the planet and create working models of intersection that foster health for adults and children? This should be a factual endeavour, not an emotional exercise.

Ultimately, it’s about doing what works within the fabric of one’s experience, forged from the truth of one’s experience – historical truth. It’s about being true to the best manifestation of that experience, having a reverence for it, honouring it – cultural identity and historical truth, what I believe would greatly foster improved health for adults and children in the Diaspora. And as far as Connected Fiction goes, it’s one of the pressing reasons why I write. You don’t have to agree, just consider.

© 2019 IC Blackman. All rights reserved.

We would like to say a big thank you to IC Blackman for this very insightful blog piece. If you have any comments or questions, please leave them in the comments section below.

You can find out more about IC Blackman and her work here or you can follow IC Blackman on Twitter.